Kolumba Museum Stands Atop A Long History of Cologne

Peter Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum is nestled in a land full of history. The city itself, Cologne, is the largest city in Germany and was one of the most heavily bombed cities in Germany during World War II. The entire city was almost completely destroyed, including the Romanesque Church of St. Kolumba, which stood on the site centuries ago. Amid the church’s rubble, the statue of the Madonna and Child remained firm as if it was a miracle. For survivors and believers, the phenomenon became a symbol of hope that strengthened them amidst the chaos—they called it the “Madonna in the Ruins.” Later in 1950, after the war ended, brutalist German architect Gottfried Böhm built a small octagonal chapel that houses the statue.

The octagonal chapel by Gottfried Böhm

The octagonal chapel by Gottfried Böhm

Zumthor’s winning design (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Zumthor’s winning design (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Nearly half a century later, Zumthor won an architectural competition to design a museum here. The museum was finally completed in 2007—when Böhm was about 87 years old, fit and well. Not-so-fun fact, Böhm was reportedly unhappy with the fact that his early work had to be shrouded by the smooth facade of Zumthor’s museum, which, considering he was a fellow designer, is understandable. While the building’s qualities are certainly different now—light can no longer enter directly through its original windows, for example—the chapel is not part of the museum’s program and continues to serve its original purpose of worship.

Inside the “Madonna in Ruins” chapel (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Inside the “Madonna in Ruins” chapel (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Böhm’s building within the new structure (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Böhm’s building within the new structure (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Zumthor designed the museum with care, constructing it atop the ruins while respecting the history of the site, protecting the remains of Gothic works, and preserving its essence. He traced the basic shape of the old church based on the remaining rubbles, continued, and patched it with a new structure. The architect also did not intervene much on the ground floor, leaving the ruins as they were, and instead installing slim cylindrical pillars to support the second floor slab and providing an elevated footbridge that allows visitors to observe the changing history of the past church building.

Elevated footbridge and slim cylindrical columns (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Elevated footbridge and slim cylindrical columns (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Exhibition rooms (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Exhibition rooms (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The museum consists of 16 exhibition rooms located on the upper floor. There is a narrow hallway as the main staircase, which provides access to connect the two floors. With an entirely plain interior, visitors will be “lost” around the exhibition rooms.

The narrow stairs (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The narrow stairs (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

All-plain interior (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

All-plain interior (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

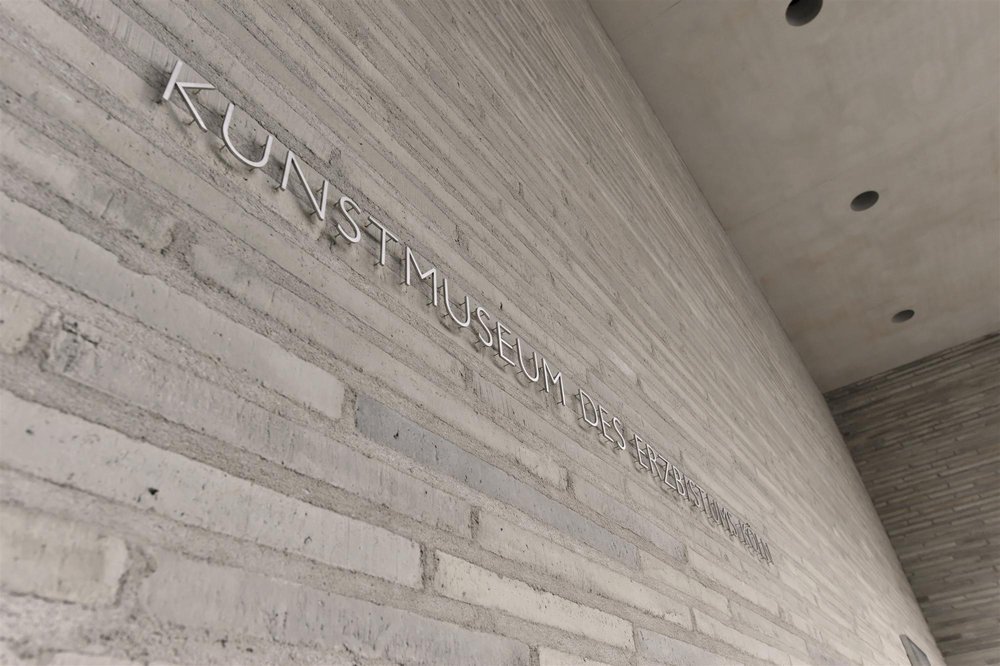

In choosing the material, Zumthor seriously took his time before finally deciding on warm gray brick combined with tufts and basalt as the perfect material to unite the pieces of the old building into a new, modern face. The bricks are articulated to be perforated to allow light to diffuse inside. The design unites fragments of old history into a new medium for conveying history as one complete architecture.

Perforated walls (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Perforated walls (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The detail of brick articulation (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The detail of brick articulation (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The unity between the old and the contemporary (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

The unity between the old and the contemporary (cr: Jose Fernando Vazquez)

Authentication required

You must log in to post a comment.

Log in